New Testament Greek Studies

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

“To train Christians in skilled servant work, working within Christ’s body, the Church.”

(Ephesians 4:12)

«Πρὸς τὸν καταρτισμὸν τῶν ἁγίων εἰς ἔργον διακονίας, εἰς οἰκοδομὴν τοῦ σώματος τοῦ Χριστοῦ.»

(Ephesians, Προς Εφεσίους, 4:12)

New Testament Greek is a program designed for anyone who is interested in learning how to read and comprehend the New Testament in the authentic Common or Koine Greek language.

During each course, at a progressively increasing level of fluency development that is achieved through structured practice and extensive drills, students build the language acquisition skills required to read, write, listen, understand, and speak Koine Greek as it is spoken by native Greek speakers.

Based on personal needs and the outcomes of placement tests, adult Greek Language Learners have the opportunity to enroll in the following beginner and intermediate courses that are designed to take the learner from the very basic vocabulary to complete mastery of authentic New Testament Greek:

NTG100: New Testament Greek Beginner Level 1 (A1)

NTG200: New Testament Greek Beginner Level 2 (A1)

NTG300: New Testament Greek Intermediate Level 1 (A2)

NTG400: New Testament Greek Intermediate Level 2 (B1)

Most students typically enter the program by starting at the Beginner level.

Example topics of instruction and learning objectives at the Beginner level include:

• Reading and writing the alphabet correctly in authentic Greek.

• Understanding accents and breathing marks.

• Learning how to use cases, numbers, and genders.

• Understanding the use of auxiliary verbs ἔχω and εἰμί.

• Using selected verbs in all persons, numbers, tenses, voices, and moods.

• Building vocabulary through reading, speaking, listening and translation drills.

• Pronouncing authentically the phonemic system of Koine Greek, including vowels, consonants, and

diphthongs.

• Reading and understanding scriptural passages, starting with the Gospel of Saint John.

• Building and using key vocabulary, including selected words, phrases, and sentences that are most

frequently encountered in New Testament Greek.

• Studying and applying grammatical rules and syntactical structures for all parts of speech, including:

definite and indefinite articles; cases and endings of masculine, feminine, and neuter nouns and

adjectives; verbs and verb tenses; usage of commonly used adverbs and participles.

COURSE OBJECTIVES AND LEARNING OUTCOMES

Instructional objectives and learning outcomes at each course level are summarized below.

These fluency-building levels are based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR or CEF) that defines teaching, learning, and assessment processes in Second Language Acquisition.

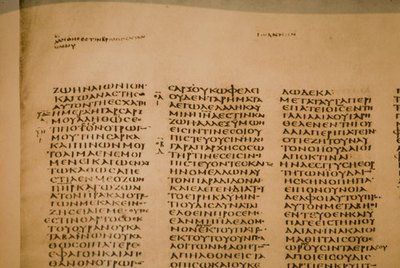

The Language of the Bible

Greek is one of the three languages of the Holy Scriptures, the other two being Hebrew and Aramaic. Understanding these languages provides a deeper comprehension of scriptural records, such as the Bible and the works of the Early Church Fathers that can lead to a stronger connection with the Christian faith.

Translation vs. Interpretation

A reader of biblical texts who is versed in Greek can draw clear distinctions between a factual translation and a hermeneutic interpretation. The factual translation opens up a wider window of understanding because it rests upon the actual meaning of the words, if adjudicated correctly, the intention of the author.

Quality of Translation

Studying Koine Greek also requires the study of English. Translations published during the 14th and 15th cent. were based on a handful of manuscripts that were available at that time. In comparison, More recent English translations are more reliable because they are based on a wider spectrum of Koine Greek grammatical and other resources.

The Greek Language in Iconography

The Greek Language is an important element of iconography. “Icon” is the transliterated form of the Greek word εἰκόνα, meaning “image”. Icons are visual representations of the people and stories of the Bible and they are a way of communicating with God through prayer.

Orthodox Christians honor or venerate icons but never worship them, for worship is due to the Holy Trinity alone. The honor given to icons passes on to the one who represented on the icon, as a means of Thanksgiving for what God has done in that person’s life.

Icons bear inscriptions, symbols and acronyms, that are written in Greek or other languages of Orthodox peoples. In the Orthodox icon-painting tradition, these inscriptions are written in contracture, which is writing a reduced form of a word, typically its first and last letters. For example, the reduced form of the name Jesus Christ consists of two pairs of letters, IC XC.

Another iconographic convention is the cruciform halo that is intended to remind Christians of the Savior’s death on the Cross and the redemptive effect upon the world.

The three visible sides of the cross within the halo are imprinted with the Greek word Ο ΩΝ, which means “I AM”. This word comes from the Greek verb εἰμί and its passive participle ὤν-οὖσα-ὄν.

Source: The Orthodox Study Bible

Notes from the Living History of Greece

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire, or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinople (modern Istanbul, formerly Byzantium). It survived the fragmentation and fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD and continued to exist for an additional thousand years until it fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1453.

During most of its existence, the empire was the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in Europe. "Byzantine Empire" is a term created after the end of the realm; its citizens continued to refer to their empire simply as the Roman Empire (Greek: Βασιλεία Ῥωμαίων, in Latin: Imperium Romanum), (Greek: Ῥωμανία), and to themselves as Romans.

The Byzantine Empire had kept Greek and Roman culture alive for nearly a thousand years after the fall of the Roman Empire in the west. It had preserved this cultural heritage until it was taken up in the west during the Renaissance. The Byzantine Empire had also acted as a buffer between Western Europe and the conquering armies of Islam. Thus, in many ways the Byzantine Empire had insulated Europe and given it the time it needed to recover from its chaotic medieval period.

After the fall of Constantinople, Byzantine scholars emigrated to Italy and other European countries. As they disseminated their Greek culture, they contributed to the development of the Renaissance in classical studies, science, the arts, philosophy, architecture, politics, and other fields of knowledge. It was this re-discovered knowledge that, subsequently, became the cornerstone of the modern Western World.